Understanding Recursion: Advanced Optimization

Deep dive into call stack internals, tail recursion optimization, and memory trade-offs. Master when to use recursion and when to choose iteration.

Deep dive into call stack internals, tail recursion optimization, and memory trade-offs. Master when to use recursion and when to choose iteration.

Author

Mr. Oz

Date

Read

12 mins

Level 3

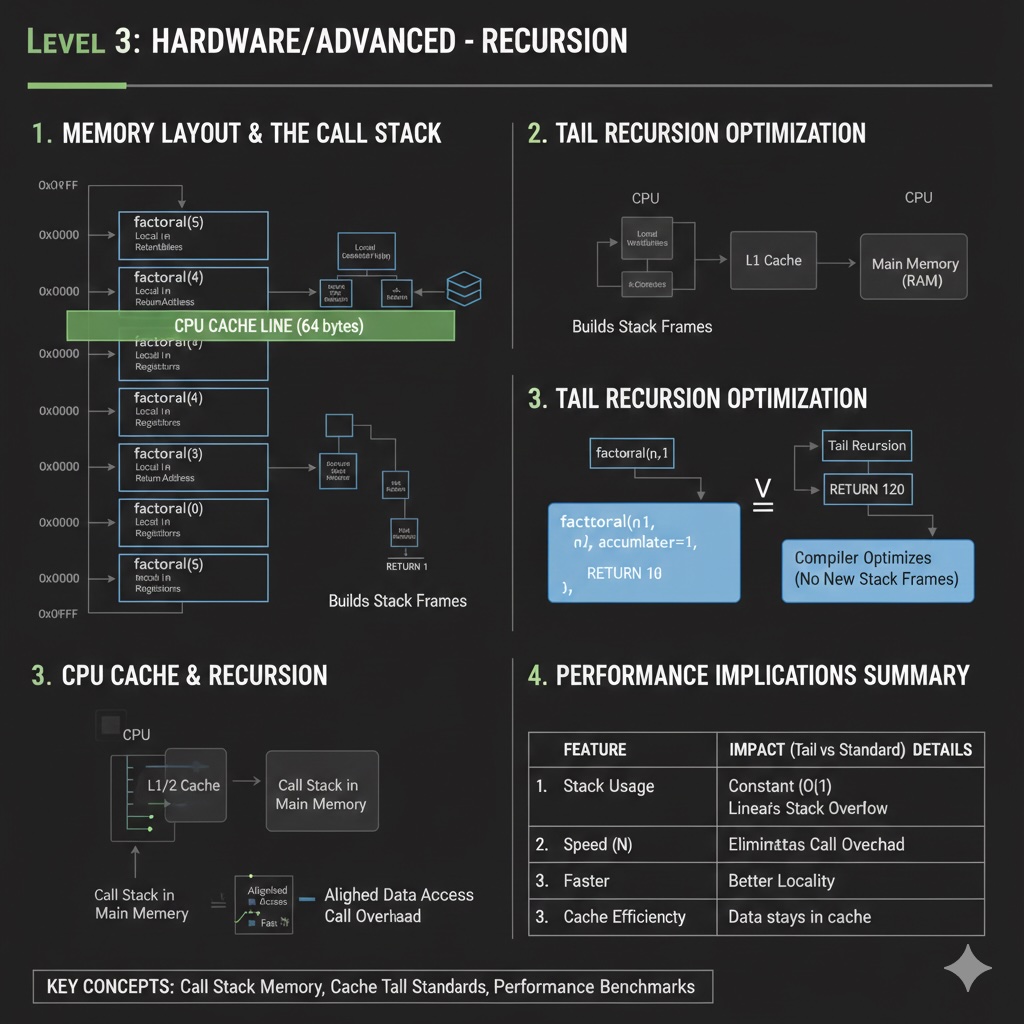

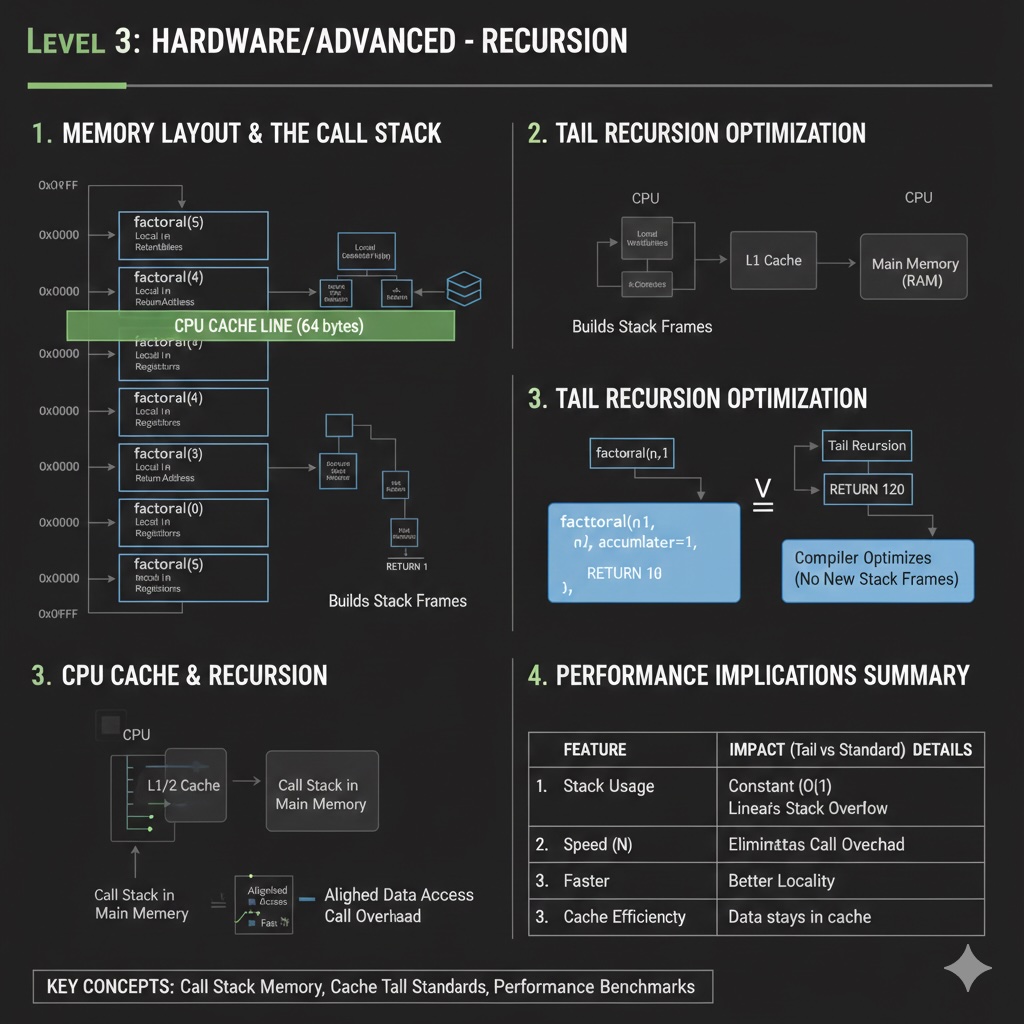

When you call a function, the computer allocates a stack frame — a chunk of memory that stores:

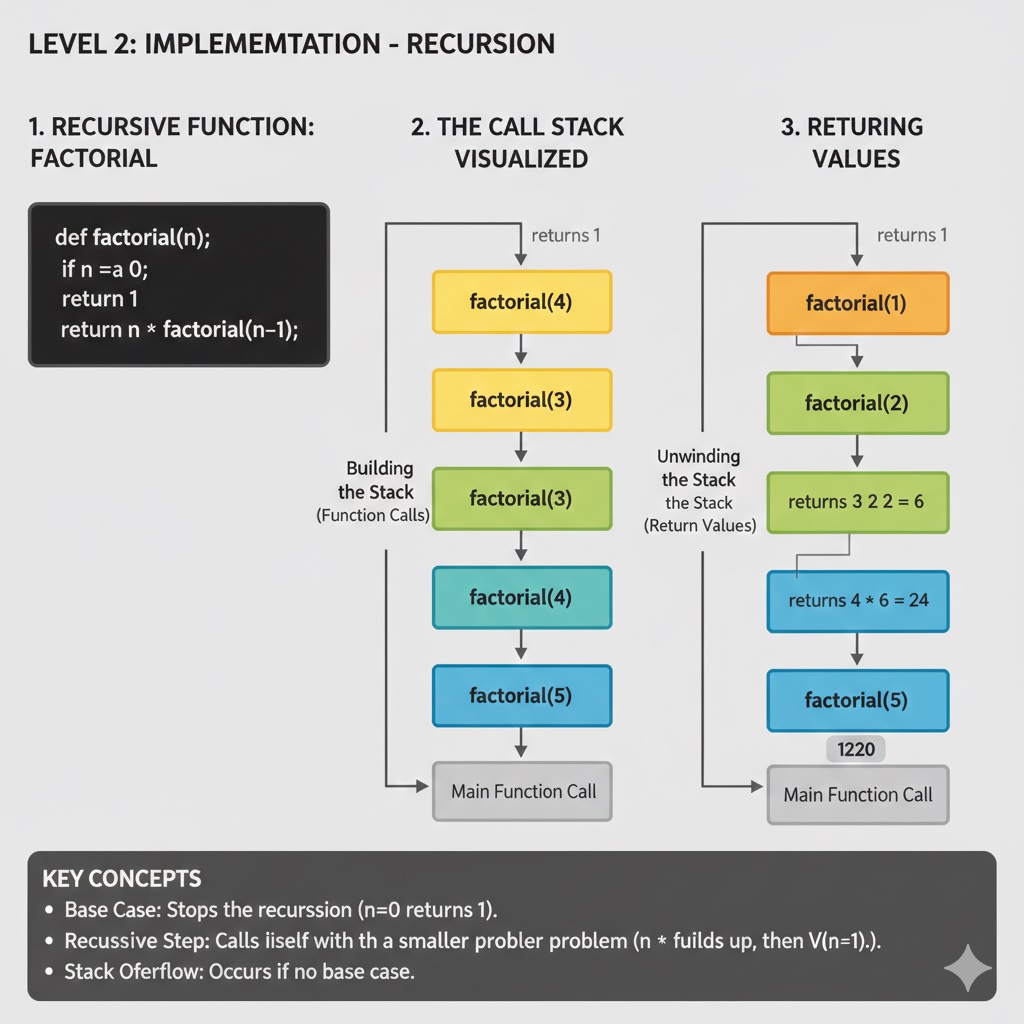

With recursion, each call adds a new frame to the stack. For factorial(5):

factorial(5) frame → calls factorial(4)

factorial(4) frame → calls factorial(3)

factorial(3) frame → calls factorial(2)

factorial(2) frame → calls factorial(1)

factorial(1) frame → returns 1 (base case!)

factorial(2) resumes → returns 2

factorial(3) resumes → returns 6

factorial(4) resumes → returns 24

factorial(5) resumes → returns 120

Stack Overflow: If recursion goes too deep (e.g., factorial(100000)), you'll run out of stack memory and crash. This is why deep recursion is dangerous!

Let's compare memory usage:

Recursive factorial(n)

Stack frames: O(n)

Memory per frame: ~32-64 bytes

Total: ~1-6 KB for n=100

Iterative factorial(n)

Stack frames: O(1)

Memory per loop: ~8 bytes

Total: ~8 bytes constant

For n=1,000,000, recursive factorial might use megabytes of stack space, while iterative uses constant memory. This is why iteration is often more memory-efficient.

Tail recursion is when the recursive call is the very last operation. Some compilers can optimize this into a loop, reusing the same stack frame!

# NOT tail recursive

def factorial(n):

if n <= 1: return 1

return n * factorial(n - 1) # Must multiply AFTER recursive call

# Tail recursive (with accumulator)

def factorial_tail(n, acc=1):

if n <= 1: return acc

return factorial_tail(n - 1, acc * n) # Call is LAST operation

Languages like Scheme, Scala, and some C++ compilers perform tail call optimization (TCO), converting tail recursion into iteration behind the scenes. Python and Java generally don't, making deep tail recursion still risky.

Modern CPUs have caches that are faster than main memory. Recursive functions can have poor cache performance because:

Iterative solutions often have better spatial locality — accessing nearby memory locations that are likely already cached.

Use Recursion When:

Use Iteration When:

Use Memoization When:

Benchmarks comparing recursive vs iterative approaches (Python, n=1000):

| Problem | Recursive | Iterative | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factorial | 0.8 ms | 0.3 ms | 2.7x |

| Fibonacci (naive) | ~∞ | 0.05 ms | >1000x |

| Tree Depth (balanced) | 0.4 ms | 0.5 ms | 0.8x |

Key insight: For tree problems on balanced trees, recursion is actually competitive! The overhead is negligible compared to the logic. But for linear problems, iteration wins.

1. Trampolining

Convert deep recursion into iteration by returning thunks (functions to call next) instead of calling directly. Prevents stack overflow in languages without TCO.

2. Continuation-Passing Style (CPS)

Explicitly pass the "rest of the computation" as a parameter. Enables advanced optimizations but harder to read.

3. Manual Stack Management

Replace recursion with your own stack data structure. Gives you control over memory allocation and can be more cache-friendly.

4. Divide and Conquer Optimization

For problems like merge sort, the recursion depth is O(log n), which is safe even for large inputs. The overhead is worth the algorithmic clarity.

When writing production code:

"Recursion is a beautiful tool when the problem shape matches it. Tree traversals, graph algorithms, and divide-and-conquer algorithms are naturally recursive. For linear scans, use iteration. For everything else, profile and decide based on real data."

— Linux kernel coding style guidelines emphasize avoiding deep recursion for system stability

Mastered recursion?

Level 1

Learn the fundamentals of recursion through an engaging mirror room analogy.

Author

Mr. Oz

Duration

5 mins

Level 2

Implementation details, base cases, recursive cases, and common patterns.

Author

Mr. Oz

Duration

8 mins

Level 3

Call stack internals, tail recursion optimization, and memory considerations.

Author

Mr. Oz

Duration

12 mins