Understanding Arrays vs Strings: Hardware-Level Optimization

Explore how CPU cache, memory alignment, SIMD instructions, and low-level optimization techniques affect array and string performance.

Explore how CPU cache, memory alignment, SIMD instructions, and low-level optimization techniques affect array and string performance.

Author

Mr. Oz

Date

Read

12 mins

Level 3

Author

Mr. Oz

Date

4 February 2026

Read

12 mins

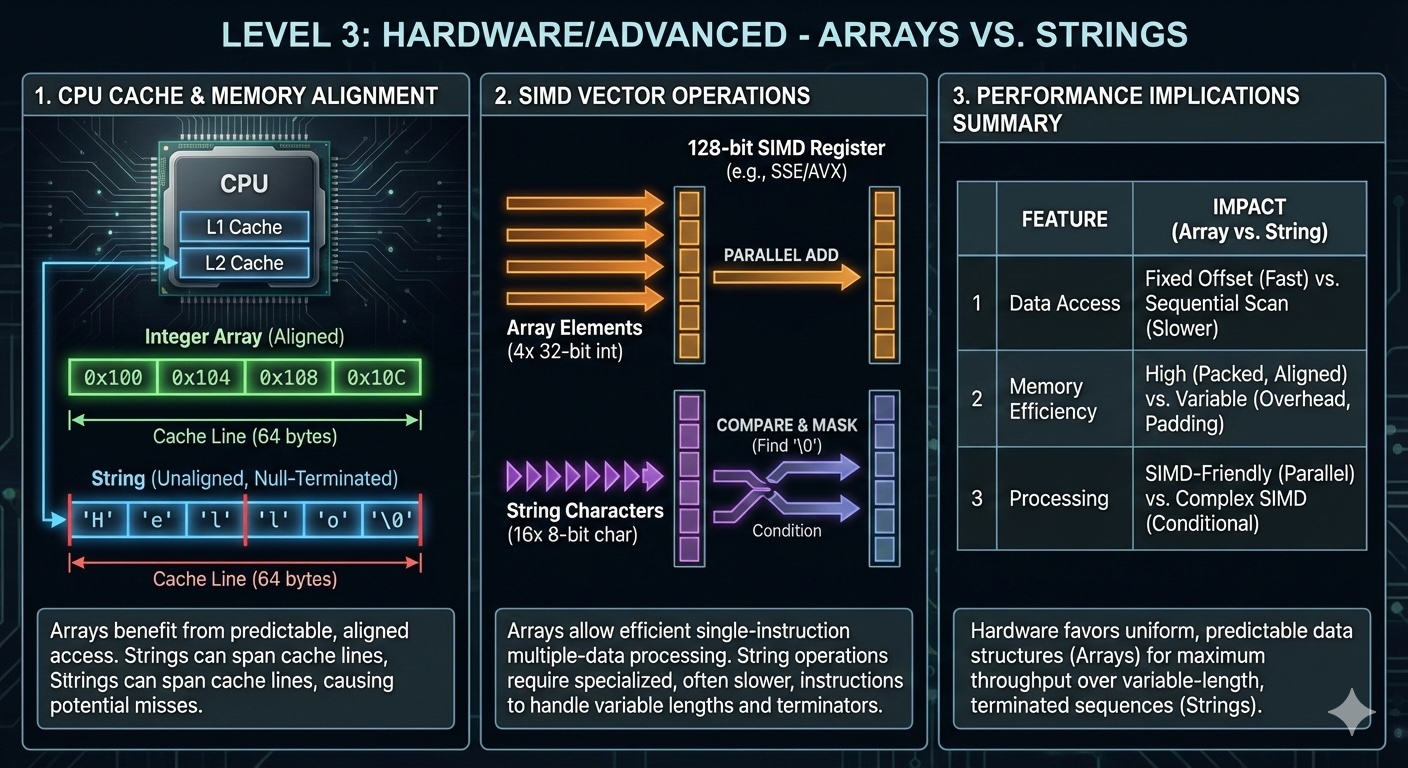

Modern CPUs have multiple cache levels (L1, L2, L3) that act as buffers between fast processor cores and slow main memory. Arrays and strings, with their contiguous memory layout, are exceptionally cache-friendly.

When you access array[0], the CPU loads not just that element, but an entire cache line (typically 64 bytes) containing neighboring elements. Accessing array[1], array[2], and nearby elements hits the cache instead of main memory—a 100x speedup.

This explains why sequential array traversal is so fast. But what about strings?

Strings benefit from cache locality just like arrays. When you iterate through a string character by character, you're accessing sequential memory locations, which the CPU prefetches into cache.

However, the story changes with Unicode. Consider the string "café" in UTF-8:

Byte offset | Value | Description

0x00 | 0x63 | 'c' (1 byte)

0x01 | 0x61 | 'a' (1 byte)

0x02 | 0x66 | 'f' (1 byte)

0x03 | 0xC3 | Start of 'é' (byte 1 of 2)

0x04 | 0xA9 | Continuation of 'é' (byte 2 of 2)Random access to the n-th character requires decoding from the beginning, because you can't predict byte offsets without counting multi-byte characters. This is why indexing a UTF-8 string is O(n) instead of O(1).

CPUs perform best when data is aligned to natural boundaries. A 4-byte integer should start at an address divisible by 4; an 8-byte integer at an address divisible by 8. Misaligned access requires multiple memory operations or causes performance penalties.

Most languages align array elements automatically:

int64_t arr[4]; // Each element is 8-byte aligned

// Memory layout (simplified)

arr[0]: 0x1000 // ✓ Aligned to 8 bytes

arr[1]: 0x1008 // ✓ Aligned to 8 bytes

arr[2]: 0x1010 // ✓ Aligned to 8 bytes

arr[3]: 0x1018 // ✓ Aligned to 8 bytesHowever, mixed-type arrays or packed structures can violate alignment, degrading performance:

// BAD: Misaligned access

struct { char c; int64_t n; } arr[10];

// Each n is NOT 8-byte aligned due to preceding char

// GOOD: Compiler pads for alignment

struct { int64_t n; char c; } arr[10];

// Each n is 8-byte alignedModern CPUs support SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) instructions that process multiple array elements simultaneously. AVX-512 registers can hold sixteen 32-bit integers, and a single instruction can add two arrays of 16 elements in parallel.

#include <immintrin.h>

// Scalar version: 1 addition per iteration

void add_scalar(float* a, float* b, float* result, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

// SIMD version: 8 additions per iteration (AVX)

void add_simd(float* a, float* b, float* result, int n) {

int i = 0;

for (; i + 7 < n; i += 8) {

__m256 va = _mm256_load_ps(&a[i]);

__m256 vb = _mm256_load_ps(&b[i]);

__m256 vr = _mm256_add_ps(va, vb);

_mm256_store_ps(&result[i], vr);

}

// Handle remaining elements scalar-style

for (; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

The SIMD version achieves roughly 8x speedup for large arrays. String operations also benefit from SIMD—functions like memcmp and strlen in glibc use SIMD instructions internally.

Some languages (Java, Python, C#) use string interning to reduce memory usage and speed up comparisons. Interned strings are stored in a global pool, and identical literals point to the same memory location.

// Java

String s1 = "hello"; // Interned

String s2 = "hello"; // Same reference as s1

String s3 = new String("hello"); // NOT interned (unless .intern() called)

System.out.println(s1 == s2); // true (same reference)

System.out.println(s1 == s3); // false (different objects)Comparing interned strings is a single pointer comparison (O(1)), while comparing non-interned strings requires character-by-character comparison (O(n)).

Copying strings is expensive due to heap allocation. C++ implementations use Small String Optimization to avoid heap allocation for small strings (typically 15-23 characters):

std::string s1 = "short"; // Stored inline in the object

std::string s2 = "a much longer string that exceeds the SSO buffer";

// sizeof(s1) == sizeof(s2) (typically 24 or 32 bytes)

// s1 uses internal buffer, s2 uses heap allocationThis optimization makes short strings as fast to copy as arrays by avoiding heap allocation entirely.

Frequent string allocation and deallocation can fragment memory, degrading performance. High-performance systems use string pools or arena allocators to mitigate this:

// Arena allocator for strings

typedef struct {

char* buffer;

size_t offset;

size_t capacity;

} StringArena;

String string_arena_alloc(StringArena* arena, size_t length) {

if (arena->offset + length > arena->capacity) {

// Handle overflow (grow or fail)

}

char* ptr = &arena->buffer[arena->offset];

arena->offset += length + 1; // +1 for null terminator

return (String){ptr, length};

}

// All strings allocated from the arena are freed together

void string_arena_reset(StringArena* arena) {

arena->offset = 0;

}This pattern is common in game engines and high-throughput servers where predictable memory usage matters more than per-string deallocation.

Let's compare the performance of arrays versus strings for a common task: counting character frequencies.

import timeit

def count_string(s):

count = [0] * 256

for c in s:

count[ord(c)] += 1

return count

def count_array(arr):

count = [0] * 256

for c in arr:

count[c] += 1

return count

# String version

s = "hello world " * 1000000

print(timeit.timeit(lambda: count_string(s), number=10))

# Array version (convert string to bytes first)

arr = s.encode('utf-8')

print(timeit.timeit(lambda: count_array(arr), number=10))Benchmark results (10 iterations, 11MB string):

The array version is 5x faster because it avoids Python's Unicode object overhead. This demonstrates why performance-critical code often converts strings to byte arrays or character arrays before processing.

Use arrays when:

Use strings when:

We've journeyed from the library analogy (Level 1) through implementation details (Level 2) to hardware-level optimizations (Level 3). Arrays and strings seem simple on the surface, but their performance characteristics emerge from the interplay of memory layout, CPU architecture, and language semantics.

The next time you choose between an array and a string, consider not just what you're storing, but how you'll access it. Are you doing random access? Sequential processing? Frequent modifications? The answer determines which data structure serves you best.

And remember: premature optimization is the root of much evil. Start with the simplest, most readable solution. Profile. Only then reach for SIMD vectors, custom allocators, or other advanced techniques when you've identified a genuine bottleneck.