Understanding Arrays vs Strings: Implementation Deep Dive

Dive into the technical implementation of arrays and strings. Learn how memory allocation, mutability, and character encoding affect your code's performance.

Dive into the technical implementation of arrays and strings. Learn how memory allocation, mutability, and character encoding affect your code's performance.

Author

Mr. Oz

Date

Read

8 mins

Level 2

Author

Mr. Oz

Date

4 February 2026

Read

8 mins

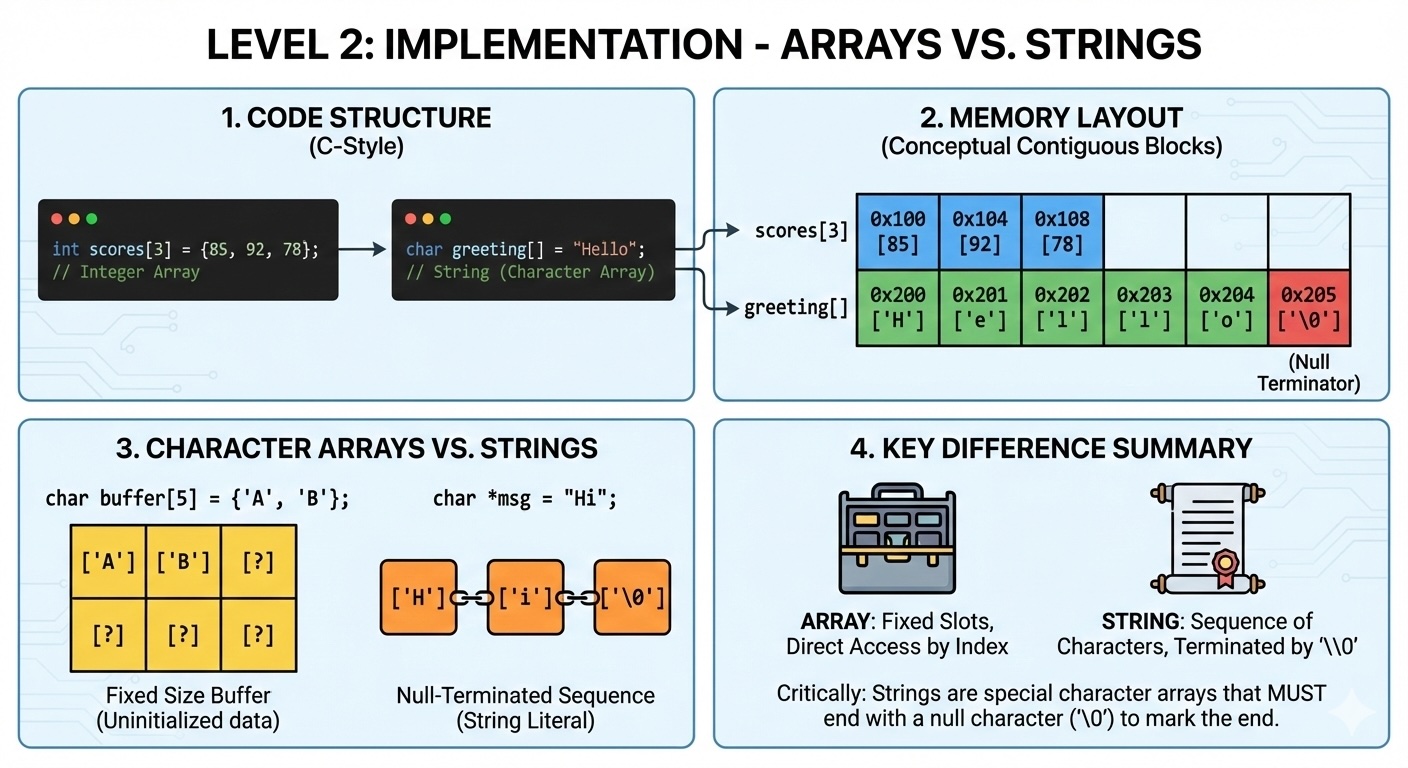

At the memory level, arrays and strings share a fundamental characteristic: contiguous memory allocation. When you create an array of integers or a string of characters, your computer allocates a continuous block of memory.

For an array [10, 20, 30, 40], memory might look like:

Address | Value

0x1000 | 10

0x1004 | 20

0x1008 | 30

0x100C | 40

Each integer occupies 4 bytes (on a 32-bit system), and they're stored sequentially. This layout enables O(1) random access—if you want the element at index 2, the computer calculates base_address + (2 × 4) and jumps directly to 0x1008.

Strings are essentially arrays of characters, but with special semantics. The string "hello" is stored as:

Address | Value

0x2000 | 'h' (104)

0x2001 | 'e' (101)

0x2002 | 'l' (108)

0x2003 | 'l' (108)

0x2004 | 'o' (111)

0x2005 | '\0' (0) ← Null terminator (C-style strings)

In C-style strings, the null character '\0' marks the end. Modern languages like Python and Java use length fields instead of null terminators, but the principle remains: strings are sequential character data.

One of the most important distinctions between arrays and strings is mutability—whether you can change the data after creation.

In Python, lists (dynamic arrays) are mutable:

arr = [1, 2, 3]

arr[0] = 99 # ✓ Works: arr is now [99, 2, 3]

s = "hello"

s[0] = 'H' # ✗ TypeError: strings are immutableThis immutability has profound implications. When you "modify" a string in Python or Java, you're actually creating a new string and abandoning the old one:

s = "hello"

s = s + " world" # Creates new string "hello world"

# Original "hello" is garbage collectedArrays don't have this limitation. You can modify individual elements without copying the entire structure.

Understanding the time complexity of operations helps you write efficient code:

| Operation | Array | String |

|---|---|---|

| Access by index | O(1) | O(1) |

| Search for value | O(n) | O(n) |

| Insert at beginning | O(n) | O(n) — creates new string |

| Append at end | O(1) amortized | O(n) — creates new string |

Notice how string operations are inherently slower because they require creating new copies. This is why building a large string by repeated concatenation is an anti-pattern—use join() or a StringBuilder instead.

Strings bring encoding complexity that arrays don't have. Each character in a string might be 1 byte (ASCII), 2 bytes (UTF-16), or even 4 bytes (UTF-32) depending on the encoding.

# Python 3: Unicode strings

s = "café"

print(len(s)) # Output: 4 (characters)

print(len(s.encode('utf-8'))) # Output: 5 (bytes)

# The 'é' uses 2 bytes in UTF-8Arrays don't have this complexity—each element is a fixed size. An array of 32-bit integers always uses exactly 4 bytes per element, regardless of the value stored.

Pitfall: String Concatenation in Loops

Never build large strings by concatenating in a loop. Each concatenation creates a new string, copying all previous characters.

# BAD: O(n²) time

s = ""

for i in range(10000):

s += str(i) # Creates new string every iteration

# GOOD: O(n) time

parts = [str(i) for i in range(10000)]

s = "".join(parts)Best Practice: Character Arrays for Manipulation

When you need to perform many modifications, convert strings to character arrays first.

# Convert to list for in-place modifications

s = "hello"

arr = list(s) # ['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o']

arr[0] = 'H' # ✓ Works

s = "".join(arr) # Convert back to stringBest Practice: Use StringBuilder for Java

In Java, use StringBuilder instead of string concatenation for mutable sequences.

// GOOD: O(n) time

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

sb.append(i);

}

String result = sb.toString();When working with strings in production, consider these factors:

In Level 1, we compared arrays to numbered lockers and strings to alphabet chains. Now you understand why those analogies hold: arrays provide direct access to any "locker," while strings require traversing the character "chain."

But there's more beneath the surface. How does the CPU cache interact with these contiguous memory layouts? Why do some string operations seem faster than others? In Level 3, we'll explore the hardware-level details that explain these behaviors.