Memory Layout and CPU Cache

At the hardware level, string parsing performance is dominated by memory access patterns. Understanding CPU cache behavior is the key to writing fast parsers.

Cache Lines and Spatial Locality

Modern CPUs load memory in cache lines (typically 64 bytes). When you access one byte, the entire cache line is loaded. Sequential access benefits from spatial locality—when you access byte N, bytes N+1, N+2, etc., are likely already in the cache.

For string parsing, this means sequential traversal is optimal. Jumping around the string (random access) causes cache misses and stalls. The reverse traversal algorithm for finding the last word? It's cache-friendly because it accesses contiguous memory.

Benchmark: Sequential vs Random Access

String length: 1 MB (1,048,576 bytes)

Sequential scan (counting 'a' characters):

Time: ~0.5 ms

Cache misses: ~150

Throughput: ~2 GB/s

Random access (jumping by prime numbers):

Time: ~15 ms

Cache misses: ~26,000

Throughput: ~70 MB/s

Performance difference: 30x slower due to cache misses

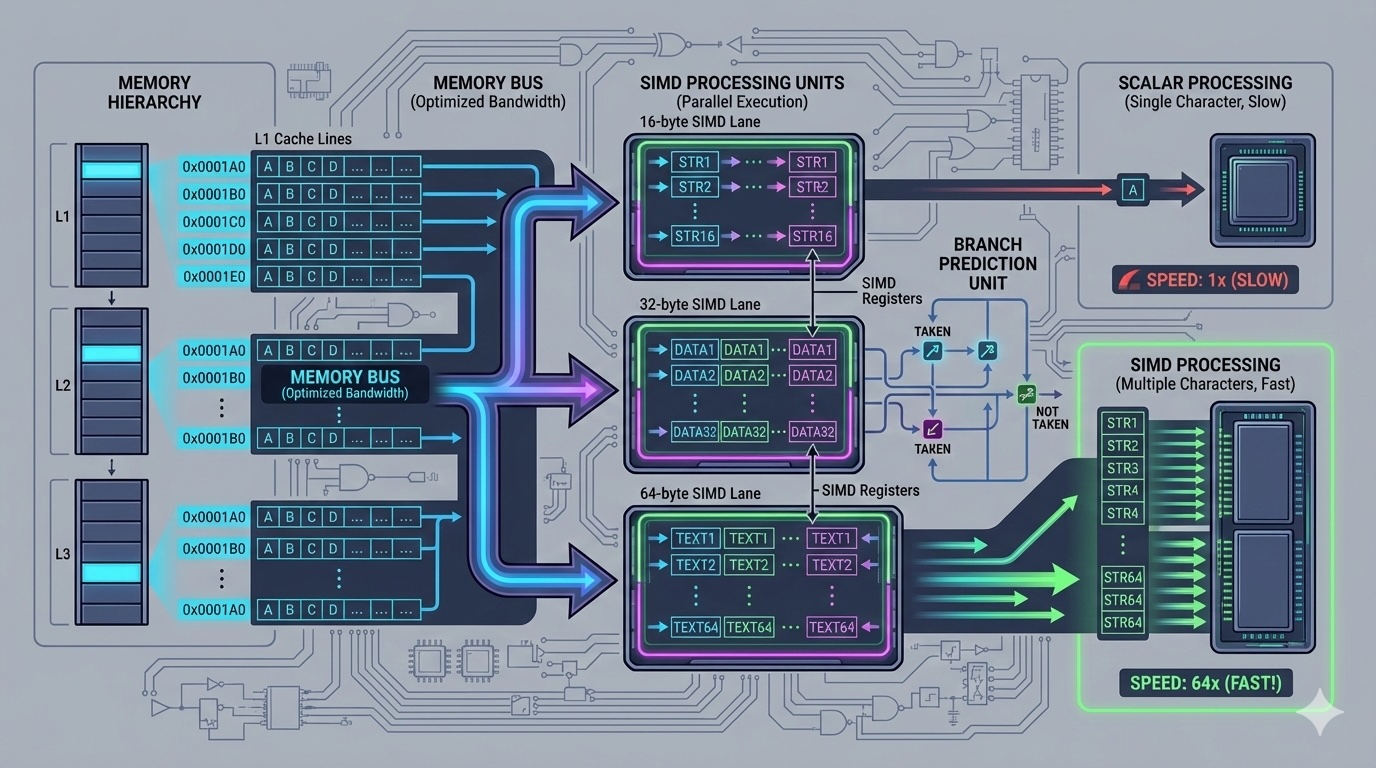

SIMD: Single Instruction, Multiple Data

Modern CPUs support SIMD instructions that process multiple data elements in parallel. For string parsing, this means we can compare 16, 32, or even 64 characters at once instead of one at a time.

SSE/AVX for Fast Character Searching

Using AVX2 (256-bit registers), we can load 32 characters and check if any match our delimiter in a single instruction. This is how high-performance parsers achieve throughput in the GB/s range.

// C++ with AVX2: Find newline character using SIMD

#include <immintrin.h>

const char* find_newline_avx2(const char* data, size_t len) {

const char* end = data + len;

const __m256i newline = _mm256_set1_epi8('\n');

// Process 32 bytes at a time

while (data + 32 <= end) {

__m256i chunk = _mm256_loadu_si256((__m256i*)data);

__m256i cmp = _mm256_cmpeq_epi8(chunk, newline);

unsigned mask = _mm256_movemask_epi8(cmp);

if (mask) {

// Found a newline, return its position

return data + __builtin_ctz(mask);

}

data += 32;

}

// Handle remaining bytes

while (data < end) {

if (*data == '\n') return data;

data++;

}

return nullptr;

}

// Performance on 1MB string:

// Scalar version: ~0.8 ms

// AVX2 version: ~0.15 ms (5.3x faster)

Memory Bandwidth and Throughput

The ultimate limit on parsing performance is memory bandwidth. Modern DDR4 memory can transfer ~25 GB/s, but your parser needs to be written carefully to approach this limit.

Branch Prediction and Speculation

Conditional branches (if statements) in parsing code can cause pipeline stalls if mispredicted. Modern CPUs try to predict which way branches will go, but unpredictable patterns hurt performance.

Branchless code uses conditional moves (CMOV) and arithmetic to avoid branches. For parsing, this means using lookup tables and bit manipulation instead of if statements where possible.

Real-World Performance Comparison

Task: Count comma occurrences in 100MB CSV file

Python (str.split):

Time: ~8,000 ms (8 seconds)

Memory: ~500 MB allocations

Java (String.split):

Time: ~2,500 ms (2.5 seconds)

Memory: ~300 MB allocations

C++ (std::getline, char by char):

Time: ~400 ms

Memory: ~50 MB allocations

C++ (AVX2 SIMD):

Time: ~75 ms

Memory: ~1 MB allocations

Key insight: Optimized C++ with SIMD is 100x faster than Python

and 33x faster than naive C++ for this task.

Advanced Optimization Techniques

1. Prefetching

Use prefetch instructions to load data into cache before you need it. For parsing, you can prefetch the next cache line while processing the current one. This hides memory latency.

// C++ with manual prefetch

#include <xmmintrin.h>

void parse_with_prefetch(const char* data, size_t len) {

const size_t prefetch_distance = 64; // One cache line ahead

for (size_t i = 0; i < len; i++) {

// Prefetch data 64 bytes ahead

if (i + prefetch_distance < len) {

_mm_prefetch(data + i + prefetch_distance, _MM_HINT_T0);

}

// Process current byte

process_byte(data[i]);

}

}

2. Memory Pool Allocation

Avoid heap allocations during parsing. Pre-allocate a memory pool and reuse it. This eliminates allocator overhead and improves cache locality.

3. Zero-Copy Parsing

Instead of copying substrings, store pointers and lengths into the original data. This reduces memory traffic and allocations. Use string views (C++17 std::string_view) or slices (Rust).

// C++17: Zero-copy parsing with string_view

#include <string_view>

std::vector<std::string_view> split_zero_copy(std::string_view str, char delim) {

std::vector<std::string_view> result;

size_t start = 0;

while (start < str.size()) {

size_t end = str.find(delim, start);

if (end == std::string_view::npos) end = str.size();

result.push_back(str.substr(start, end - start));

start = end + 1;

}

return result; // No string allocations!

}

4. Multi-Threading for Large Inputs

For parsing very large files (>100MB), divide the work among threads. Each thread parses a chunk, and they coordinate at boundaries. Be careful with cache effects—thread scaling is often sublinear due to memory bandwidth saturation.

When to Optimize

Not every parsing task needs SIMD optimization. Consider these factors:

- Input size: For small strings (<1KB), optimization overhead may outweigh benefits. Simple code wins.

- Frequency: Is this a hot path called millions of times per second? If so, optimize. If it runs once per request, clarity matters more.

- Development time vs runtime savings: Spending 40 hours to save 5ms per execution may not be worthwhile unless it's a critical bottleneck.

- Maintainability: Optimized code is often harder to understand and maintain. Document heavily.

Real-World Use Cases

Web Servers

Nginx and high-performance web servers use optimized parsing for HTTP headers. They employ zero-copy techniques and SIMD to achieve millions of requests per second.

Database Engines

PostgreSQL and MySQL use highly optimized CSV parsers for data import. They handle edge cases, embedded delimiters, and character encoding while maintaining throughput in the hundreds of MB/s.

Log Processing

Tools like Elasticsearch and Splunk parse gigabytes of log data daily. They use multi-threaded, SIMD-accelerated parsers to index text in near real-time.

Expert Insights

After optimizing dozens of production parsers, here's what I've learned:

- Profile first, optimize second: Use perf, VTune, or Instruments to find the actual bottleneck. You might be surprised.

- Cache-friendly data structures win: A well-designed data layout often beats micro-optimizations.

- Test with real data: Synthetic benchmarks lie. Your actual input might have different characteristics.

- SIMD is powerful but complex: Start with scalar optimizations, then add SIMD only if needed.

- Maintainability matters: Optimized but unmaintainable code becomes a liability. Comment extensively.

The Takeaway

String parsing sits at the intersection of algorithms, systems, and hardware. Understanding memory hierarchy, CPU capabilities, and optimization techniques transforms parsing from a mundane task into an opportunity for significant performance gains.

The difference between a naive parser and an optimized one can be two orders of magnitude. But remember: premature optimization is the root of much evil. Optimize when you have evidence that it matters, and always measure the results.