Understanding Hash Tables — Hardware-Level Deep Dive

Memory layout, CPU cache performance, collision resolution internals, and when to use hash tables vs alternatives.

Memory layout, CPU cache performance, collision resolution internals, and when to use hash tables vs alternatives.

Author

Mr. Oz

Date

Read

12 mins

Level 3

At the hardware level, hash tables are a fascinating interplay between memory layout, CPU cache behavior, and algorithmic efficiency. Let's look under the hood.

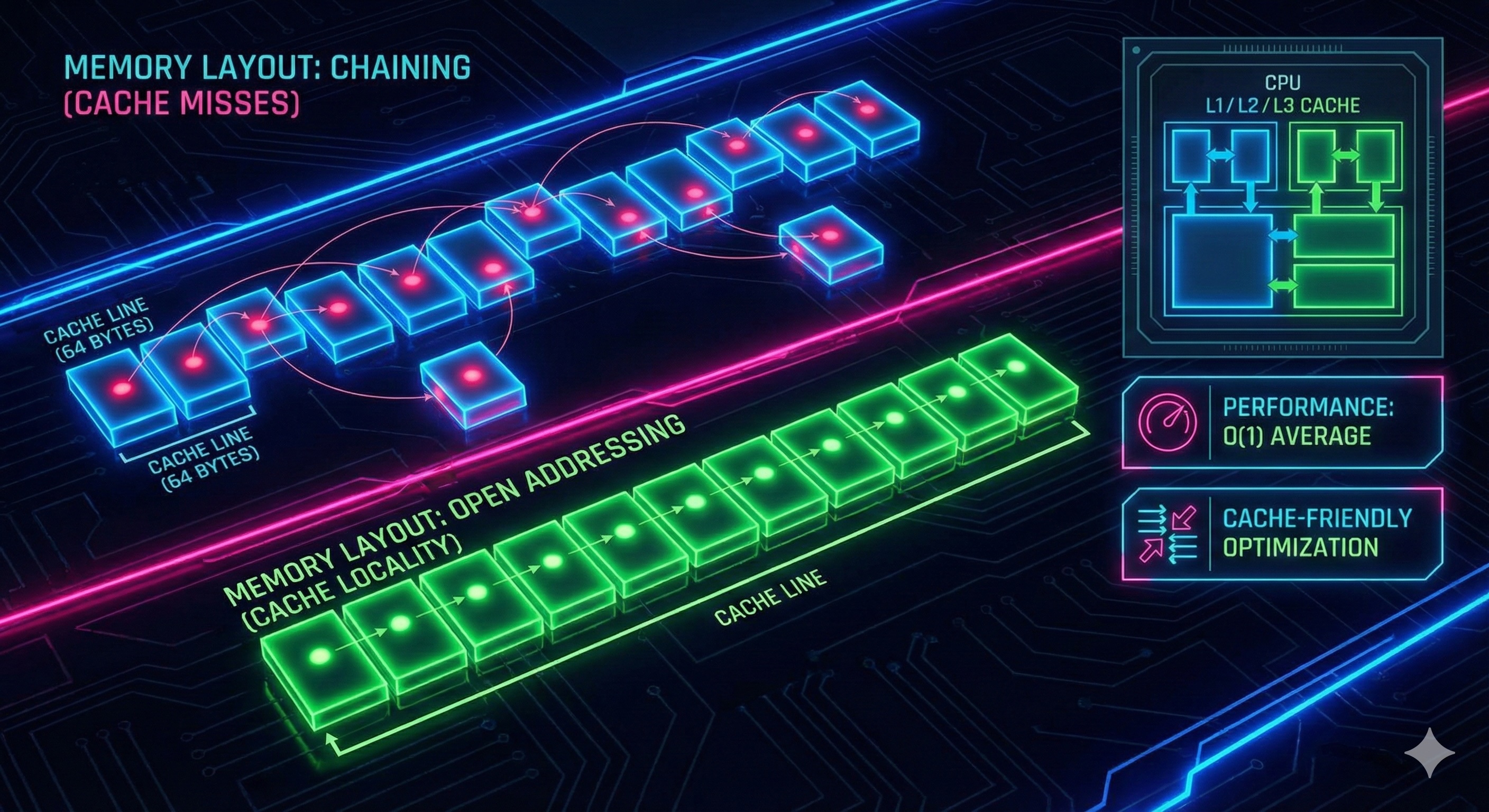

Modern CPUs have multi-level caches (L1, L2, L3). Hash tables can be cache-friendly or cache-hostile depending on implementation:

Cache line insight: When you access memory, the CPU loads a whole "cache line" (typically 64 bytes). Open addressing benefits from this as consecutive buckets share cache lines.

// Open addressing - better cache locality

struct Entry {

Key key;

Value value;

bool occupied;

};

Entry table[SIZE]; // Contiguous memory!Java's HashMap is a sophisticated implementation that evolved over time:

The tree-ification threshold is carefully tuned: converting to tree has overhead, so it only happens when beneficial.

When a hash table resizes, ALL entries must be rehashed to new bucket positions. This is expensive!

Pro tip: If you know the final size, initialize with that capacity to avoid resizes!

# Python: Pre-allocate for better performance

d = {} # Starts small, resizes multiple times

d = {k: v for k, v in data} # Better: knows final size

# Java: Pre-allocate

Map map = new HashMap<>(1000); // Initial capacity Real-world performance for 1 million lookups:

| Data Structure | Lookup | Memory |

|---|---|---|

| Hash Table (avg case) | ~50 ns | ~32 MB |

| Hash Table (worst case) | ~50 ms | ~32 MB |

| Sorted Array (binary search) | ~500 ns | ~8 MB |

| Balanced Tree (std::map) | ~200 ns | ~40 MB |

Note: Worst-case hash table performance occurs with pathological hash functions and poor resizing.

Hash tables excel at lookups, but consider alternatives when:

PostgreSQL and MySQL use hash indexes for equality lookups. B-tree indexes are more common due to range query support.

Python's `functools.lru_cache` uses a hash table to cache function results. Redis and Memcached are essentially distributed hash tables.

Compilers use hash tables to track variable names, function names, and scope information during parsing.

Routing tables map IP addresses to next-hop destinations. Fast lookups are critical for line-rate packet processing.

The quality of your hash function directly impacts performance. A poor hash function causes clustering.

Metrics for hash function quality:

Industry standard: SipHash, xxHash, and CityHash are modern, high-quality hash functions used in production systems.

For concurrent access, traditional locking can be a bottleneck. Lock-free hash tables use atomic operations:

Real-world: Java's ConcurrentHashMap uses striped locks (multiple locks, each covering a subset of buckets).

Mastered hash tables?